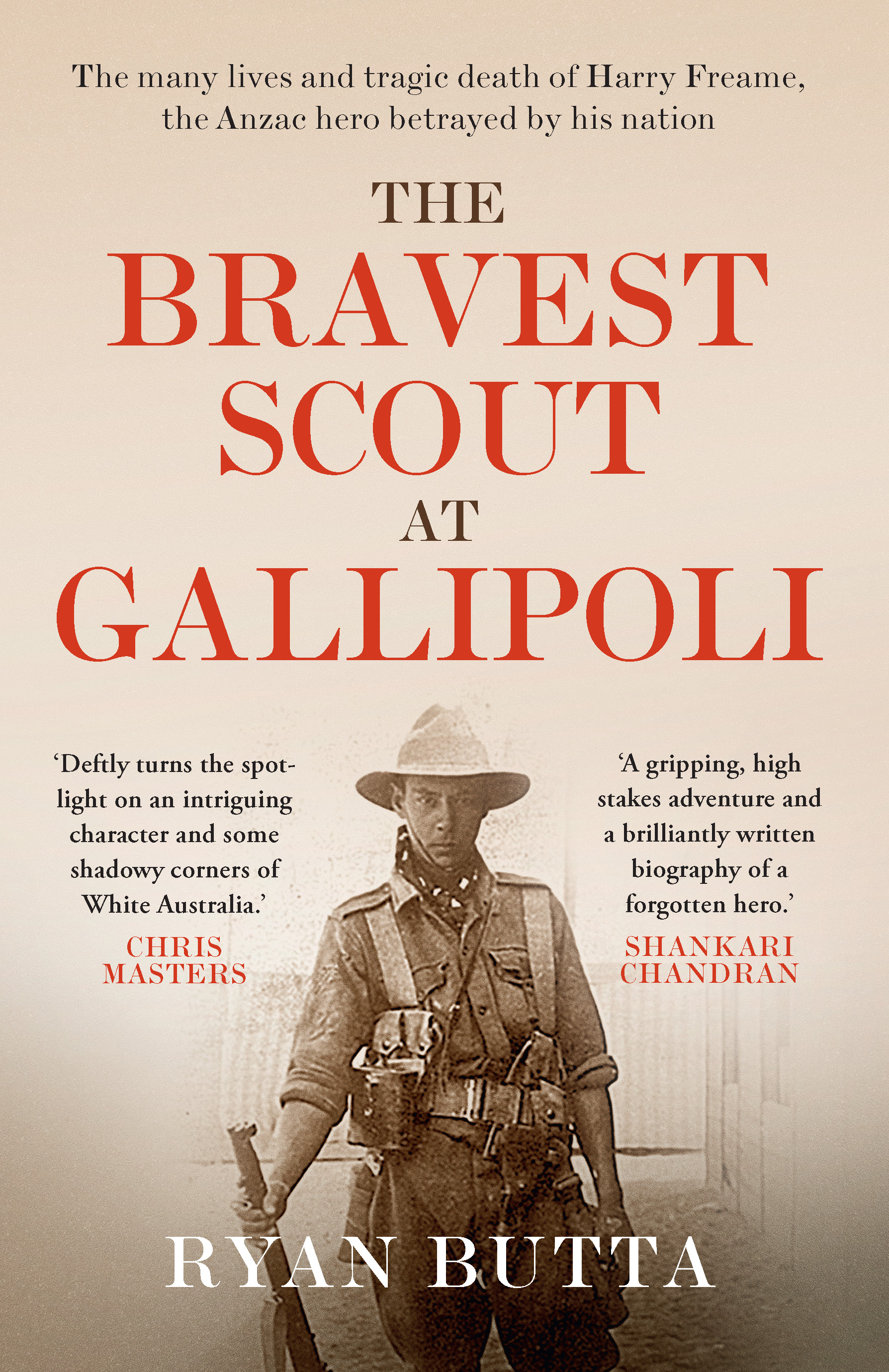

The Bravest Scout at Gallipoli

The many lives and tragic death of Harry Freame, the Anzac hero betrayed by his nation

By Ryan Butta

Published by Affirm Press

RRP $34.99 in paperback | ISBN 9781922992086

Harry Freame’s story begins in Japan in 1880 as the son of an Australian father, who died before he was twelve months old, and a Japanese mother.

He and his siblings were effectively stateless because of his father’s complicated history. His father had abandoned his pregnant wife in the then colony of Victoria and headed to Japan where he reinvented himself as a teacher of English in a country desperate to modernise.

Harry left Japan at the age of 16, having first absorbed the lessons of a Samurai warrior from his step-father.

Not unlike his father before him, Harry Freame’s passage through life was marked by versions of the truth.

Returning to Australia and enlisting in 1914, he dropped his age by five years and changed his place of birth from Japan to Kitscoty, a remote village in central Canada, as a way of explaining his dark skin and attesting to his British citizenship. Within a few short months, he would be landing on the shores of Gallipoli, being proclaimed a hero for his exploits.

It turned out his scouting instincts were ‘uncanny’ and he became the first Australian soldier to win the Distinguished Conduct Medal at Gallipoli. He risked his life again and again to scout the battlefield, reporting invaluable intelligence and relieving stranded soldiers. Some say he should have got the VC but didn’t because he was half-Japanese, a fact he tried hard to conceal.

After the war, Harry became a soldier settler and champion apple grower.

But in the lead-up to World War II, he was recruited into Australian intelligence. Extraordinarily, this fact was leaked by the Australian press, and the Japanese secret police tried to assassinate Harry not long after his arrival in Tokyo in 1941. He died back in Australia a few weeks later.

Harry was the first Australian to die on secret service for Australia, but his sacrifice has never been officially acknowledged. Only now is his full life story being understood.

There must always have been a tension between his two identities: Australian Anzac hero and his Japanese alter ego, an outsider in a country at war with his birthplace.

Ryan Butta encourages us to consider that he might have seen the role of interpreter to the Australian legation in Japan as a way of finally expressing his Japanese self, setting aside the risk he faced when his name was exposed in the press. He had a led a life of high adventure. It was to end, ultimately, from an attempted garrotting.

VERDICT: Butta has pieced together the life of a man whose exploits deserve recognition.